|

[I personally want to thank all of our dedicated and loyal subscribers who have inquired about how to send much-needed donations directly to me here in Venezuela. At present the only way to send money intended for my personal use is through the FTW website or by mail so stating. I am working on setting up an account here and we’ll let you know when one has been established. In the meantime, FTW itself needs your continued financial support. There are things like layoffs and cutbacks that we don’t want to consider, but they are on the table.

What you can do to help is to place orders for my newest DVD “Fear and Present Danger”. I consider it my best work since “The Truth and Lies of 9-11”. This is the video of my hour-long April address in New York called “The Paradigm is the Enemy”, easily the most important speech I have ever written. It is a clear and original way of looking at a world in great turmoil. The second part of the DVD is a very short message I delivered extemporaneously on camera in Ashland, Oregon on June 30th, just a day before I realized that I was going to leave the US forever. As the words left my mouth I was sensing that a turning point had been reached for all of us. You can almost see the decision being made. What I warned of is already coming to pass.

As fate would have it, I am now in a place where I might be of some service as a reporter at just the right time. I hope that I am equal to the task. – MCR]

[On August 25 when I wrote “Latin America De-Constructs The Tapeworm” as a subscriber story, I had no idea that Mike Ruppert would soon be writing a story that would amplify my comments and enhance them with photos. In this article, Mike takes us with him to his new life in Caracas, revealing the Venezuela that has existed for decades as well as the “nuevo patria” (new country) that the government of Hugo Chavez Frias is creating.—CB]

VENEZUELA

Caracas, Part I

by

Michael C. Ruppert

© Copyright 2006, From The Wilderness Publications, www.fromthewilderness.com. All Rights Reserved. This story may NOT be posted on any Internet web site without express written permission. Contact admin@copvcia.com. May be circulated, distributed or transmitted for non-profit purposes only.

Statue of Bolivar

September 12th 2006, 2:25PM [PST] - CARACAS – Now I begin to write about one of the most important and influential countries in the world today, Venezuela. It is certainly the most influential nation in the Western Hemisphere outside of the United States, and it doesn’t take a great many tea leaves to see that perhaps the greatest battles over its sovereignty are yet to come; battles in which the United States is no longer a superpower but evenly matched against a rising people, a rising region, and a leader who have been besting it both internationally and inside the country since 1998.

The outcome of these battles may in part decide the future course of human history. They will determine whether the Empire can secure the energy it needs to keep up the internal appearance and external semi-reality of control for just a little while longer. The longer the Empire stays in some form of control, the worse the chances are for the rest of the world. And that much further down the path of “consume rather than conserve” will we have ventured as a species.

The stakes are higher now. With Peak Oil dominating foreign policy, five areas of the world are emerging as critical: The Middle East, West Africa, Canada’s Alberta tar sands, The Caspian Basin, and Venezuela’s Orinoco belt. In all five regions US hegemony and influence have been successfully challenged, even in Canada where China has secured portions of the paltry one million barrels a day of production and has plans to build a pipeline to Canada’s Pacific coast.

The United States alone consumes 22 million barrels per day so the production numbers from these very expensive and hard-to-develop regions will never come close to even offsetting a global decline rate now estimated at six to eight per cent a year. The species is already fighting over scraps.

In three regions (sans West Africa and the Middle East) are the heavy and extra heavy, “sour” oils that, while not permitting global economic growth to continue, will serve as very expensive parachutes for some passengers on the bright, shiny and ever-more-rickety airplane of human civilization. It is now clear that the airplane will not be brought in for an early safe landing, far from its destination of infinite global economic expansion. The strategies pursued by the world’s dominant economic and military power, the US, before and since 9-11 have pre-destined that the airplane will crash and that those without parachutes will go down with it.

It is against this backdrop that the government of Hugo Chavez is seeking re-classification of its extra heavy Orinoco bitumen (not previously counted as oil) as part of its official reserves. On paper at least, this would give Venezuela larger reserves than Saudi Arabia. This does not mean that the world’s energy crisis is suddenly, magically solved. In fact, it may actually indicate that the Peak Oil crisis is far worse than most have suspected.

OPEC production quotas are calculated as fractions of stated reserves. Again, at first glance, this seems like a great wish. If Venezuela’s reserves were re-calculated then they could just turn on the tap and produce enough for everyone, get rich and we’d all be happy, right? That’s what OPEC did to bankrupt the Soviet Union in the 1980s by driving down oil prices. But if wishes were horses then beggars would ride, and this is not the 1980s – when such a thing as spare capacity actually existed – and worldwide demand was twenty million barrels a day less than today.

Extra heavy oils are extremely expensive to produce, and they only become viable over the long term when prices are at roughly $60 a barrel or higher. Even then, they only become real after the investment of tens of billions of dollars and years of construction. Venezuela’s extra heavy oil is similar to that found in the Canadian tar sands, but, thanks to the warmer climate and the fact that the reserves are deeper in the ground where temperatures are hotter, they flow more freely. That’s the good news and the bad news. In Alberta giant dump trucks and bulldozers are used to literally strip mine the tar which is then washed with steam, produced by burning copious quantities of ever-dwindling natural gas. It must be drilled for in Venezuela. Either way it takes a lot more energy to get a lesser quality of energy out of the ground than with conventional oil.

The standard way to extract Orinoco heavy oil has been to drill five wells. Four are used to inject steam (remember it takes energy to boil water) and force the oil up the fifth shaft. Newer production techniques are being developed and implemented, and it has been estimated that about 600,000 barrels per day of Venezuela’s total daily output of around three million barrels is from this region. Venezuela is aggressively pursuing these technologies since its own conventional oil production peaked about a decade ago.

Some 55 leading oil-producing nations around the world have entered permanent decline. Hugo Chavez himself has acknowledged the reality and the gravity of Peak Oil in the press. So has his good friend and mentor Fidel Castro.

In Canada, after twenty years and more than $10 billion in investment, the most Canada can produce is a million barrels per day (Mbpd) from its tar sands. Best estimates project that by 2020 and another $20 billion in investment, Canada may be able to produce three million barrels per day. So what?

This, in a world consuming between 84 and 85 million barrels per day and where annual depletion is between five and six million barrels per day, per year and accelerating. Global depletion is only going to get worse and may fall off a cliff; especially when and if Saudi fields start collapsing from overproduction like Kuwait’s Burgan field did last year. Mexico’s super-giant Cantarell, the world’s second largest field is also in steep decline. The North Sea is in decline. Norway is in decline – even as CNN runs specials about how Norway is investing its oil wealth for use after the oil “runs out”. Russia is in decline. Saudi Arabia has almost certainly entered decline, although the Saudi government will engage in any possible (sometimes ludicrous) deception to hide this fact.

The salient question is what will Venezuela’s position in the world be when, because of its ability to produce and refine its extra heavy oil, it surpasses these countries in overall production at levels far below today’s output. What happens when tomorrow’s big dog (Venezuela) is about half the size of today’s big dog (Saudi Arabia)?

After extracting it you must refine extra heavy oil, and there are very few complex refineries being built, especially in the US, to handle it. It only takes about three to five years and between $100 and $200 million to build a complex refinery capable of turning oil into gasoline.

So Chavez’s agenda has another and deeper significance. Anticipating the day when Venezuela may well be, as a result of its heavy oil, the world’s top oil producer (it is now ranked 5th) – after the imminent decline and collapse or decline of Saudi, Russian, Iranian, and Kuwaiti production – at numbers of around four to possibly six Mbpd, the country with the largest reserves may well be able to dictate policy, even impose a depletion protocol on the world as a whole. It is a certainty that Hugo Chavez will not endorse a policy of infinite growth, nor will he agree with Dick Cheney that the “[North] American way of life is not negotiable.”

Saudi production appears to have already peaked at just under ten million barrels per day, and Saudi’s aggressive use of secondary and tertiary recovery water and gas injection risks the collapse of the geologic structures housing their reserves sooner than need be. The reshuffling of the world’s top oil producers will likely begin within Hugo Chavez’s next term as president, and global production will be far less than it is today no matter what fantasy solutions are offered to queasy markets and Prozac-ingesting consumers.

As we will see in the coming months, Hugo Chavez seems to understand the balance that need be struck between selling Venezuela’s oil outside Latin America to keep cash flows going and making sure that enough stays here for the benefit of his Latin American “neighborhood” which is coming to be defined by initiatives like Mercosur, Petrocaribe, and the “Bolivarian Revolution”. These initiatives and the regional pride instilled by Chavez are uniting Latin America like no other region of the world. This is the re-localization that FTW has so long advocated but on a continental scale. For example, the government is supporting the creation of Endogenous Development Centers and is also promoting the creation of direct-democratic communal councils, as well as thousands of urban land committees.

One of the greatest delights for the palette of any visitor to Venezuela is its coffee. A new friend quoted a writer as describing it once as a “ray of condensed sunshine”. Venezuela consumes 98% of its coffee crop inside the country and for good reason. It’s that good. Perhaps it will someday be that way with Venezuelan oil, not because it is that good, but because it is that essential. This is the one thing, the one example that the United States cannot tolerate or allow. The entire essence of US foreign policy, whether it is called “free trade” or “development” can be summed up by its essential and eternal quest to take resources from one part of the world cheaply and transfer them to its control for the profit of shareholders outside of the source country.

Funny but Community Councils sound an awful lot like Catherine Austin Fitts’ Solari Circles. One man’s New Socialism is another woman’s New Capitalism. In this age of Orwellian “newspeak” one must study to find meaning and truth. Money’s truths have always hidden behind many veils. Whatever one calls them, these models will prove to be the only way to survive Peak Oil after fuel prices and conflict have made it impossible to ship essential commodities, consumer goods, and especially food, over great distances. There are ten calories of hydrocarbon energy in every calorie of food consumed on the planet.

The coming battles in Venezuela will be dark, nasty, underhanded, likely bloody and very different from those in other parts of the world, at least as the US initiates and wages them. Venezuela is a battleground of ideas, ideologies and vision. It was throughout Latin America that the Rockefellers injected their corporate and financial business models starting in the mid-1930s when oil was discovered in the Orinoco, and a Standard Oil yacht steamed a young, awestruck Nelson Rockefeller into the beauty that is South America.

THE ROCKEFELLERS

There is an entirely different overt and covert flavor to Latin America than there is in any other part of the world. It is at once both beautiful and deadly.

The Rockefeller philosophy of letting the third world have “some” of the profits (mostly in the hands of ruthless oligarchies not inclined to share them) has been replaced by Latin America’s just demands that nations own, control and distribute their own resources. For all the decades that have passed since the 1930s, things have not changed as much as might be hoped.

In 1939 Nelson Rockefeller, as he fought to stave off a hybrid Communist-nationalist movement to seize Standard Oil assets in Venezuela, struggled to get his managers to listen to him. He argued that “some” benefit should go to the Venezuelan people to keep them working and to protect Standard Oil properties from nationalization. Venezuelan oil workers at the time lived and worked in sub-human conditions of poverty, disease, and hunger. In Thy Will be Done one of only two books I brought with me as I left the states, author Gerard Colby described the situation.

Nelson’s presence was not yet appreciated by either local Creole [a Standard Oil subsidiary] managers or anticommunist nationals like Rómulo Betancourt, editor of Ahora and leader of the left-of-center opposition party, Acción Democrática. But it could not be ignored. ”After looking over his vast oil properties,” Betancourt wrote of Rockefeller, ”…he will return to his office atop Rockefeller Center, to the warm shelter of his home, to resume his responsibilities as a philanthropist and Art Maecenas. Behind him will remain Venezuela with its half million children without schools, the workers without adequate diets…, its 20,000 oil workers mostly living in houses… better called overgrown matchboxes.

Nelson’s Creole also left behind a thick sludge of oil over the surface of Lake Maracaibo [in the west]. In December, for the second time that decade, the oil scum caught on fire, the shacks that oil workers had built on stilts over the lake exploded in flames, roasting hundreds of families alive.1

In 1998, the year that Hugo Chavez came to power as a result of a democratic election, something similar happened. A Caracas taxi driver named Luis took me to a dead-end alley perched over the edge of a steep hillside near La Cortada deep inside the western barrios. He pointed through some trees some 600 yards across the valleys and the freeway leading to the airport and drew my attention to a large gravity-fed gasoline storage facility perched on an opposing hilltop. The tank farm was directly above hundreds of barrio dwellings. In Spanish he told me, “It blew up in 1998, and everyone below, thousands of people, were incinerated.”

Gasoline Storage Facility

This gasoline tank farm blew up in 1998 just before PDVSA was nationalized. There were homes immediately below it then and all who lived there were incinerated. Since PDVSA’s nationalization more money is spent on safety.

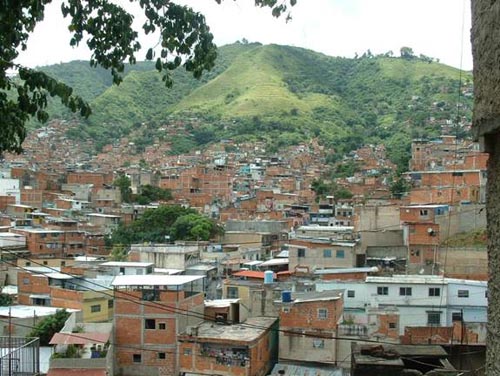

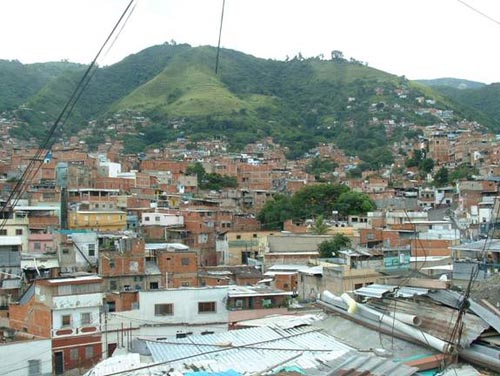

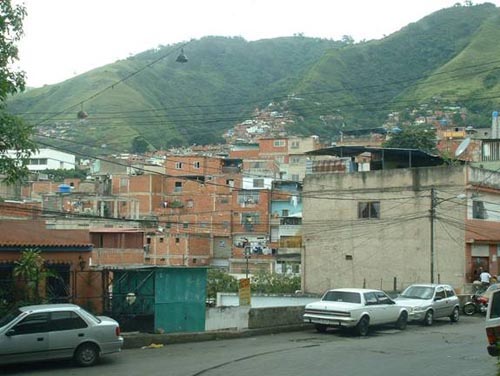

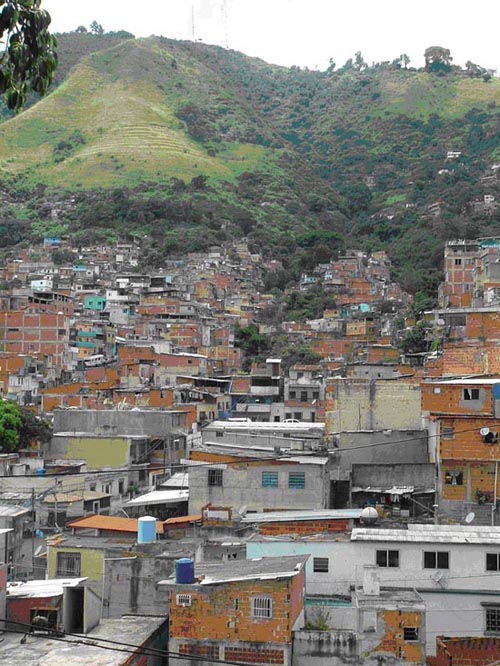

Barrio

Barrio

The first thing one sees of Caracas when leaving the clean, modern Maiquetía airport on Venezuela’s northern coast are the barrios.

Caracas’ barrios are “homes” built mostly of reddish brown brick, cement, and cinder blocks with corrugated tin or metal roofs. Many have no water or electricity. I have heard estimates that as many as a million-and-a-half people live in them, and they continue – the only human structures the eye can see – for more than a mile-and-a- half, climbing up the steepest hillsides imaginable. There is no reassuring city skyline in the distance, and one wonders what will appear on the other side of the imposing hills.

Because they are all that one can see, except for the thick, velvet-green mountains that must be crossed to get inland to the city, the barrios give a first impression that Caracas is frighteningly poor and dangerous. Barrios are common in all large Latin American cities – a direct byproduct of economic and political life engineered first by colonial powers and then by giant US, British and German corporations. Cheap labor.

In other Latin American cities barrios aren’t as visible by design. They give a bad impression to turistas and investors. On the high plateau giving rise to Mexico City for example, the barrios are far away from the airport and out-of-sight, just as they are in Los Angeles. The geography that defines Caracas demands honesty. It leaves few places to hide.

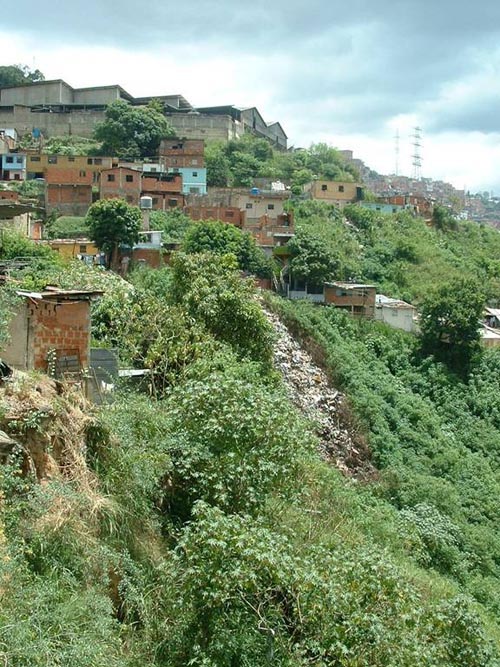

Barrio With Trash On Hillside

Caracas’ barrios are far more deprived of human comfort and services than anything we ever called a barrio in East Los Angeles. In their own way they symbolize the honesty and clarity of the government of Hugo Chavez. Caracas itself seems to say, “This is how the world is really structured; the four and five-star hotels, the high-rise towers, the fancy restaurants and SUVs rise up from the backs of the poor. They come from the raw materials of land and jungle and people. This is the way the world is, and this is the way we deal with it and see it in Venezuela. All of these parts must be made to see each other if we are to live together or to live at all.”

I saw them from a distance for the first time after being awake for more than thirty hours on the day I arrived. My first thought was “Blade Runner” in the jungle. Nowhere is there recognizable planning; the structures look as compact as the dense, ultra green vegetation surrounding them. There seems more order in the vegetation.

The barrios were here before Hugo Chavez Frías, and they will be here after him. However, almost all who live there enthusiastically agree that conditions have improved dramatically since he became president.

In 2002 and 2003 Venezuela went through one of its most wrenching recessions, due to the coup attempt and the shutdown of the country’s oil industry. There was very little oil wealth to chase in those years. An oil boom took place in 2004, but today, new oil wealth is being distributed more equitably than ever in the nation’s history.

The barrios are justly regarded as unsafe by most inhabitants of the city, and street crime is common. Drugs are easy to find. Most of the smaller residential “streets” are remarkably free of litter. But, within them, where the smaller roads converge at crossroads, where there are bus stops, the trash often blocks entire lanes and impedes intersections. Throughout the city, long lines for the patchwork of free-market, unregulated buses are hundreds-long during rush hour. The people wait patiently and in seeming good spirits.

But also within the barrios one finds schools and clinics, new since Chavez became president, and they are having a positive impact. In these clinics one can find some of the thousands of Cuban doctors (some of the best in the world) who have come here in solidarity and also as repayment for Venezuelan oil. Not everything in Latin America is priced in US dollars.

Aside from the chronic poor and the criminals within the barrios are many poor Chavistas who constitute a core of mass support that saved the Chavez government from a bloody US-funded and assisted coup attempt in 2002. These people will take to the streets in a heartbeat if their revolution is threatened. Miraflores palace – where Hugo Chavez is said to shun the ornate quarters reserved for a head of state in favor of more Spartan digs appropriate to the military ranks from which he rose as a paratrooper – sits conveniently close to the western barrio of 23 de Enero. Tens of thousands of Chavista poor can be at the palace to protect it from another coup within minutes. Hugo Chavez has two armies, and they are both loyal.

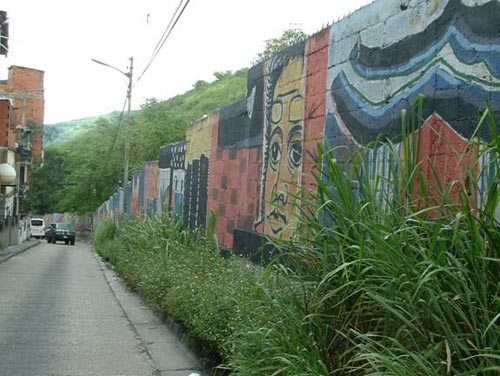

There is a love affair between Chavez and the peoples of the barrio and the graffiti and art to be found there, some of it awesomely beautiful, attest to this.

Barrio Art

Some of the art deep inside the barrios is breathtaking.

The hillsides, rising as much as 3,000 feet, do not allow you to see the narrow roads and paths that people walk, ride motorbikes, or drive on everyday to get to work or for simple shopping. Small bodegas and street vendors make the acquisition of daily bread and sundries possible. From the freeway leading into town it appears as if there is literally no way to get in, let alone around or out. But Venezuelans do it every day.

A common complaint from the opposition is that Chavez’s Bolivarian Revolution is not doing enough to put money in the hands of the poor. This is a strategy all-too-familiar in Latin cultures from Mexico to Chile where the Rockefellers, US corporations, and puppet dictators have come and gone leaving the basic neo-colonial system unchanged for many decades. Chavistas argue that Hugo Chavez and the people themselves understand the difference between handing out money and handing out education, medical care, and institutional, societal and cultural reform. Especially in Latin cultures, things take time. So when candidates come and go, like the current presidential challenger Manuel Rosales, promising to hand out debit cards with cash before this December’s election, there is no hoard of uneducated, greedy, thoughtless hands clamoring to sell the future for a quick and temporary payoff.

Poverty here is acquiring wisdom.

What Hugo Chavez’s Bolivarian Revolution has come to represent for all of Latin America is the future. The most common Chavista slogans are: “A different world is possible” and “A better world is possible”. How Chavez and the rest of the world will deal with Peak Oil and what it means for the expectations of the poor, who do not yet grasp that their dreams may never come true, remains for all to see. But I would bet my last Bolivare that Chavez and his government are thinking about it and planning for it like Norway is.

Another Barrio Scene

Exchange rates for Venezuela’s currency, the Bolivare, range from about 2150 (official) to 2500 to one US dollar on the black market.

|